Not a Pitch

The Best Teams Form Around Truth, Not Persuasion

Not a Pitch

Not a Pitch

It was February 2019 when I was offered the opportunity to become Director of Quality Engineering for the organization where I worked—a role I had spent nearly eight years working toward. It should have felt triumphant. Instead, it felt complicated.

At the time, Quality Engineering was a pillar of its own, separate from Software Engineering, which had its own pillars, directors, senior directors, and vice presidents. The Quality Engineering organization stood alone, and I was one of four or five directors. Above us was a Senior Director—soon to become a Vice President—overseeing a team of roughly 1,300–1,400 software quality engineers.

I had aspired to this role since joining the company on December 5, 2011. I came in as a Senior Software Quality Engineer, an individual contributor, and over the next eight years worked my way through the ranks to finally reach that goal. The moment, however, was bittersweet.

I was told the role was between me and another person—someone I didn’t believe was performing at my level. My pride took a hit. I questioned why my hard work and performance were being compared to someone who, in my view, was not delivering at the same standard. That sting deepened when I later learned from him that the role had been offered to him first—and that he had turned it down.

I spoke with friends, considered other opportunities, and spent about a week and a half debating whether to accept the role. In the end, I decided to swallow my pride and make the most of the opportunity. There was one condition, though: I had to accept this other person as a direct report, help him grow, and allow him to retain ownership of his existing team.

Even then, I didn’t realize it, but I was beginning to learn a lesson that would later shape how I lead and hire:

The most important work isn’t about convincing people to follow you—it’s about being honest enough that the right people choose to walk alongside you.

From February 2019 until March 2021, I led and grew my organization to 115 engineers, structured under four managers. We were responsible for five different products. Every three months, we held in-person staff meetings, traveling to offices in North Carolina, the Czech Republic, and India. I took the role seriously as an opportunity to shape the organization into what I believed a Software Quality Engineering group should be.

At the time, I felt we were still heavily reliant on waterfall methodologies, despite claims to the contrary. My team often found itself acting as gatekeepers—deciding whether a product was ready to ship. That role made me uncomfortable. It ran counter to the agile, embedded, and collaborative culture I wanted to foster.

Balancing that vision with the expectations of upper management proved difficult. My manager expected strict enforcement of quality standards, while I pushed for a more integrated and flexible approach. That tension was already challenging—and then COVID-19 arrived.

During this period, I set myself a personal mission: to meet every associate, either in person or virtually. I wanted to build real connections and flatten the organization as much as possible. COVID complicated those plans, but I persisted, continuing what I half-jokingly called my “world tour.” I eventually met most of the 115 individuals, listening to their stories and building relationships.

At the same time, my family life was deeply affected. As a father of three daughters, I felt a responsibility to keep spirits high amid the uncertainty. One of the hardest moments for me was watching my father—a lifelong symbol of strength—struggle with his fear of COVID. Hearing about my team members’ losses, loneliness, and resilience was both heartbreaking and inspiring.

By October 2020, it became clear that I was facing a significant roadblock. Despite my efforts, the lack of support from my manager made it evident that I wouldn’t be able to realize the vision I had for the organization. After consulting with a career coach, I made the painful decision to leave the role. I had worked hard for the title of director, and the thought of walking away was deeply uncomfortable—but once I committed to that decision, I began exploring new opportunities.

One of the Software Engineering directors I admired had built a highly agile and successful team. He had long been a role model and mentor, and we began discussing potential paths forward. At the time, the organization was going through rapid changes, and he advised me to wait.

In early January 2021, while staying at my mother’s house and writing to clear my head, I received a message from him about an open position. I applied immediately.

After three interviews—which happened fairly quickly—things suddenly went quiet. Days turned into weeks with no updates. It wasn’t that I’d been ruled out; rather, the organization was in flux, with priorities and reporting lines shifting rapidly behind the scenes.

I also learned I was competing against a senior Software Engineering manager, someone well-known and respected within the organization. That felt like a disadvantage. By the middle of February, I knew I had to act.

During that time, one of the original interviewers became the hiring manager for the very role I was pursuing. She reached out and explained that, given the changes, she felt it was important to speak again—this time through a different lens. We agreed to one more interview. The conversation went well. I answered her questions thoughtfully and walked away feeling I had done everything I could. Still, when she asked me her last question, I genuinely couldn’t tell whether I had the job or not.

By then, the uncertainty was taking its toll. My own manager was pressuring me to vacate my role as quickly as possible, and I was emotionally exhausted from living in limbo. So instead of waiting yet again, I decided to be fully transparent.

I told her, heart to heart, that I felt I had answered all of her questions and that I believed I had what she was looking for. I said I didn’t want to go another day not knowing where things stood. And professional to professional, I asked plainly: What is it going to take for me to get this position?

She paused, smiled, and told me—right then and there—that I had the job.

Relief washed over me as I realized a new chapter in my career had begun.

Leaving my previous role was abrupt. My former manager didn’t ask for a transition period. There was no goodbye, no acknowledgment. It hurt—but I chose to put my ego aside and focus on what lay ahead. I was about to build a new team, apply my hiring and leadership philosophy, and take on a project that genuinely excited me.

You see, over my years as a Director in Quality Engineering, I had developed a habit of continuously scouting talent. After a decade in the organization, identifying strong candidates had become second nature.

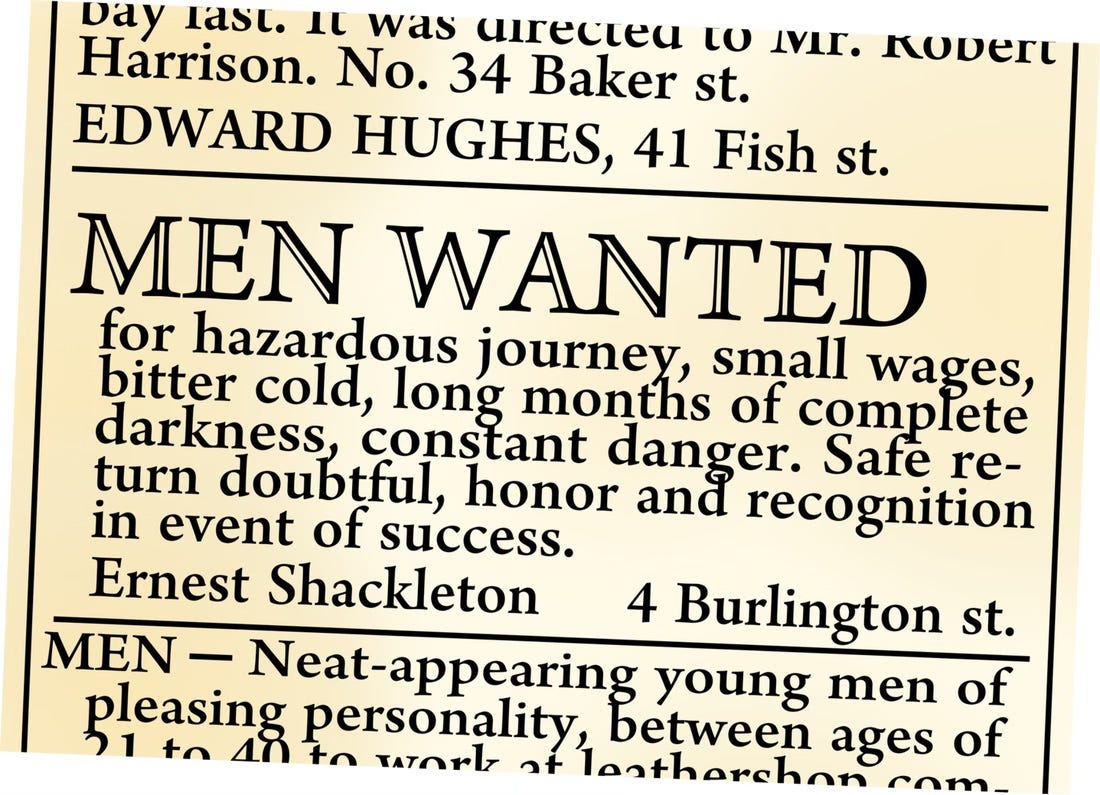

I drew inspiration from Ernest Shackleton’s famous recruitment strategy for his Antarctic expedition. Shackleton set brutally honest expectations, attracting people drawn to challenge rather than comfort. I approached hiring the same way. We were venturing into unknown territory, and I needed people who would lean into uncertainty.

That approach resonated with me—not just because of the honesty, but because it respected people’s agency. It gave candidates a clear picture of what they were signing up for and, just as importantly, a graceful opportunity to opt out if it didn’t align with what they wanted from their careers.

Hiring isn’t about convincing people. It’s about aligning truths.

I began reaching out to people I’d connected with over the past year. I had a stack of strong résumés—people I’d always wanted to bring into the company. As a Director, however, I wasn’t necessarily hiring individual contributors directly, which meant my role was often to recommend candidates rather than make the final hiring decisions myself. Despite my recommendations, some of these candidates didn’t make it through the interview process. I never fully understood why, as they were highly talented individuals with the grit, determination, and emotional intelligence to strengthen the team.

I reached out to several of them immediately. My goal was to build a diverse team by bringing together people whose skills complemented one another, rather than hiring based solely on similar skill sets. My manager and I aligned on this approach, so I began sending emails and doing the legwork myself. Unlike many peers who rely on talent acquisition for sourcing résumés and scheduling interviews, I chose to handle this directly since I already had a clear list of people in mind. It was easy to set up initial 30–45 minute conversations where I could assess whether each candidate would be a good fit for the team.

The very first candidate I contacted was a Brazilian woman living in Rio de Janeiro. I had spoken with her about a year and a half earlier and was confident she would be an excellent addition. That initial interview went very well, and we agreed to bring her on board. As it turned out, all of the interviews I scheduled initially were with women, and each one proved to be an incredible fit for the team.

One change I’d made over the past few years was deciding not to be the sole decision-maker in hiring. I had learned that by the time I recommended someone, I was already biased in their favor. To counter that, I set up diverse interview panels that included people from different functional areas such as documentation, program management, and product management. Occasionally, my manager joined these panels as well. After each round of interviews, the panel would meet to discuss whether we should move forward with a candidate. I also provided a shared document for capturing notes and feedback, ensuring that every voice was heard in the decision-making process. I believe that being deeply involved in hiring is one of a leader’s most important responsibilities.

Then came a surprise. We had initially been given 18 months for research and development, with no formal deliverables—just time to experiment. That expectation changed quickly. Leadership asked us to deliver a minimum viable product (MVP) within three months. At that point, we had no engineers hired and only an architect on board. It was a shock. My original vision of building a balanced, diverse team suddenly felt at risk.

Still, I was determined to stay true to that vision. I proposed bringing in strong mentors—Principal Software Engineers from other departments who could work closely with the new hires and provide hands-on guidance. This approach allowed us to continue hiring for potential and diversity while still meeting aggressive short-term goals.

Our first hire—the Brazilian woman—joined the team, and soon after, two more Brazilians, both women, came on board. I spent hours every day following leads and reviewing referrals. One candidate had once aspired to be a commercial pilot. Another climbed utility poles by day while training to become a software engineer at night. By the end of our initial calls, I knew I had found diamonds in the rough. Within a couple of weeks, we had our first core group in place. I created a structured onboarding plan for each person, pairing them with principal mentors and outlining a week-by-week roadmap to help them ramp up and succeed. Not every hire worked out—external factors sometimes intervened—but overall, we built a stable, high-functioning team.

Beyond staffing the team, I was also stepping into a new environment, working with people who had already been collaborating on the project for some time. During my first program call, I sensed immediate tension. The group included quality engineers, documentation specialists, program managers, product managers, and software engineers from various dependent teams. An Agile practitioner facilitated the meetings, but there was visible friction among the engineering groups, each operating with its own priorities and timelines.

Recognizing this, I began scheduling one-on-one conversations to build rapport and better understand what each person needed. As the “new guy,” I leaned into that role—asking questions that might have seemed obvious or even naïve, but that helped break down barriers and encourage openness. To my surprise, many others had the same questions but had been hesitant to ask them. These conversations allowed me to surface and address underlying dysfunction, helping move the group toward a more collaborative and functional way of working.

Within the first five months, a team of newly hired engineers successfully built a fully functional, integrated prototype that gave customers a web-based interface to create and manage customized immutable operating systems based on our company’s primary Linux distribution. These operating systems could then be deployed to edge environments such as train systems, submarines, oil rigs, and automobiles.

The solution had to fit seamlessly into both new and legacy services, which required the team not only to communicate exceptionally well with one another, but also to navigate the turbulent waters of intra-team politics, along with frequently competing and conflicting priorities and timelines. Along the way, it became clear that the prototype would need to “stick around” longer than originally planned, serving as a bridge until the functionality we developed could be absorbed into existing projects or adopted by new ones.

By the time we completed our first year together, it felt as though we were operating like a well-oiled machine—but instead of cogs, we were a team of founders who shared common values, goals, and a strong sense of ownership. I remember saying during team calls that we would become the bar by which other teams in the company would be measured for efficiency and effectiveness, a belief that was genuinely shared across the group.

From the moment a code change was accepted and merged to the moment it was delivered to customers, the entire software delivery lifecycle took roughly 20 minutes. Every step—running unit tests, scanning for security vulnerabilities, building containers, and deploying—was fully automated. Our team routinely pushed around 80 such changes to production each month, compared to an average of 10–15 releases from other teams.

Eventually, the time to transition what we had built to other teams caught up with us. Slowly, I witnessed the complete dismemberment of the team I had so carefully built over two and a half years, as we began handing off code and responsibilities to others. This period coincided with an especially difficult chapter at work, during which I once again found myself in conflict with a new manager due to deep differences in style and philosophy—particularly around how to manage projects, support teams, and keep people motivated.

My ENFJ personality (often called “The Protagonist” in the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator) initially helped me resist rebelling outright under a new regime of persistent micromanagement and mounting work stress. Instead, I redoubled my efforts to rise to the occasion, continuing to act as a buffer to protect my teammates from the daily barrage of requests that treated them as fungible resources—people who could be shifted and moved at any moment without regard for their personal goals or aspirations.

Despite my best efforts, I eventually found myself completely burned out for the first time in my career. Waking up and showing up to work each morning became a chore. I had to deliberately put on a façade just to get through the day, while internally I was quietly burning down to a dry husk.

Coincidentally, I had a minor accident at the office that forced me to take a 30-day leave of absence to recover. That time away gave me space to reflect deeply on my career and on what I wanted from my life more broadly. For the first time, I began seeing a psychiatrist, who helped me reframe my thinking and recognize that I needed to help myself first before I could help anyone else. Using an analogy she shared with me, I realized I had been allowing others to drink from my cup long after it had run dry. Looking back, the warning signs were there long before I was willing to see them.

When I returned from my leave of absence, things moved quickly. Part of my team was transferred to another group under a different manager. Two of our most well-known engineers were reassigned to work on a temporary proof of concept under my manager’s direction. I, meanwhile, was reassigned to take over a different team—one responsible for monitoring and maintaining portions of our customers’ infrastructure. Less than four months later, I was reassigned yet again to another team. In short, stability vanished just as quickly as we had created it.

To say the road wasn’t easy would be an understatement. There were many moments when I considered turning in my badge and looking for a position elsewhere—perhaps at a startup where I could have more autonomy and freedom to innovate and build truly successful, diverse teams. Every time I felt close to the brink, I was reminded that, in true ENFJ fashion, I can endure far longer than most people expect when others depend on me—when my team’s morale or sense of direction is at stake. ENFJs persevere when challenges are tied to people, values, or a larger purpose.

For the past year and a half, I’ve been quietly building up my current team while slowly bringing together the group of teammates I had carefully hired earlier—the people I’ve always thought of as our “Founders” in spirit. We’ve come a long way from where we were in the summer of 2024, when I first joined them, to where we are today. There have been many challenges—more than I care to share publicly—and periods when it felt like we were all burning the candle at both ends.

The new year promises to place us even closer under the microscope. All eyes will be on us as we navigate the spotlight and transition from being second-class citizens to becoming a core part of our solutions—while simultaneously helping our teammates grow, develop, and pursue their career aspirations, keeping pace with the supersonic speed of the AI software space, and improving our own processes to meet the higher expectations now placed upon us.

Looking back, I genuinely believe that every team I’ve been part of—or had the privilege to lead—could fill the pages of its own article or chapter. Not because of grand achievements, but because of the countless lessons—both positive and painful—that we experienced together. Each team offered unique opportunities for growth and learning, and I’m deeply grateful for the chance to work alongside so many talented individuals.

Many of these colleagues became lifelong friends, and our shared journeys have enriched both my professional and personal life, making the entire experience far more meaningful and rewarding. What I carry forward isn’t just gratitude—but a clearer sense of what kind of leader, teammate, and human I want to continue being.